The VAGUS Nerve (Part I): What Does It Do and What Happens When It Goes Bad?

At-A-Glance

- There are twelve Cranial Nerves (CNs), “cranial” meaning that the nerves emerge from the cranium (head/brain), and most of the CNs are responsible for our senses, vision, hearing, balance, taste, smell. The 10th cranial nerve (CNX) is the Vagus Nerve.

- The Vagi (pl. vagus) are powerful and vitally important nerves that control the respiratory, digestive, and cardiovascular systems as well as the viscera (internal organs). The vagi are responsible for regulation of many critical functions, including heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, swallowing, digestion, speech, cough, and airway protection.

- After exiting the brain, the vagi descend in the neck behind the tonsils and enter the chest, and they they are vulnerable to infection or injury, which can adversely alter nerve function, that is, cause neuropathy, a term that means “sick nerve” … and the adjective, neurogenic, means “sick-nerve-caused.”

- The most common vagally-mediated neurogenic symptoms are voice change, loss of vocal strength and pitch-range, vocal fatigue, effortful speaking, voice-use pain, abdominal bloating, nausea, vomiting, heartburn, indigestion, sore throat, burning throat, chest pain, back pain, asthma, chronic cough, cardiac arrhythmias, and fainting — ALL vagally-mediated.

- In this post, Part I of III, I will try to help you understand vagal function and dysfunction. In Parts II & III, I will present what I know about the clinical consequences of vagal neuropathies that affect the phonatory (voice), neurological, gastrointestinal (GI), respiratory, and cardiovascular symptoms.

Dear Reader: Until now, there has been a paucity of information about the vagus nerve and vagally-mediated neuropathic syndromes. This topic is impactful and this blog is expansive; therefore, I have divided it into three parts. This is Part I, but the three parts taken together are my “White Paper on the Vagus Nerve”… rather like a medical tell-all from an experienced physician. Prego! Most of what I know is here, including clinical observations that have not been previously published. -Dr. Jamie Koufman

The vagus nerve “anatomically numbered” is the tenth of twelve Cranial (coming from cranium/head) Nerves. It is a vital nerve, as no other nerve in the body compares with the broad physiologic influence of the vagus … for one thing, if you cut both, you die.

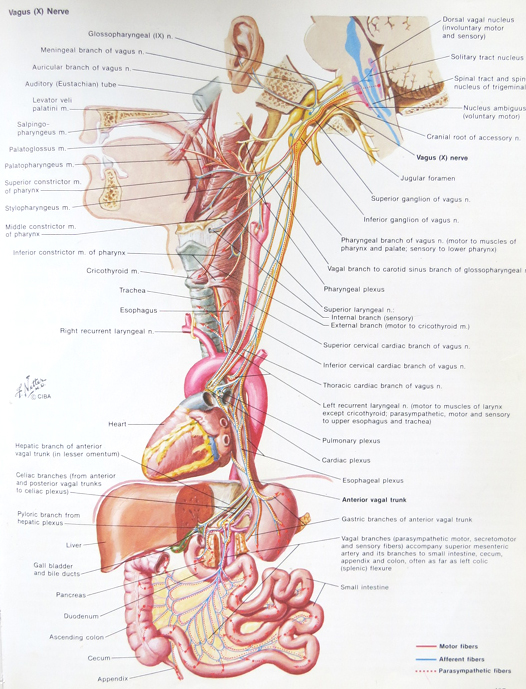

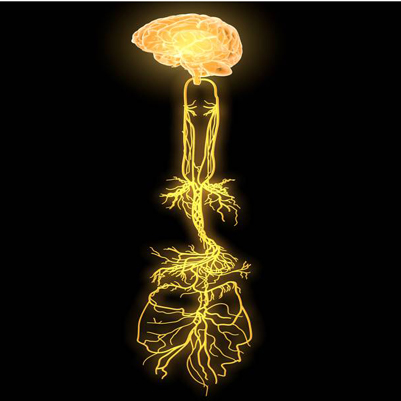

The vagi (pl. vagus) control the respiratory, digestive, and cardiovascular systems as well as the visceral organs; see the photo above. The vagi are responsible for the regulation of critical functions, including heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, swallowing, digestion, speech, cough, and airway protection.

I have clinical and research experience with thousands of patients with vagal neuropathies; and much of the material herein has not been previously reported in peer-reviewed medical journals. (I would, but in semi-retirement, I lack the resources to do so.) Besides, I often have difficulty getting my work published in “prestigious” medical journals, because the ideas are considered too controversial, even radical.

This post is about what happens when the vagus nerves get damaged or sick. The meaning of vagally-mediated neurogenic (“sick nerve”) syndromes is almost self-explanatory; it means “sick-vagus-nerve-caused problems.”

Is the Vagus the Seat of the Soul?

On the Internet, there’s a lot of discussion about the psychological and metaphysical, even spiritual nature of the vagus … at the very least, its link to wellness. And there are “training methods” and (breathing and voice) exercises for vagus nerve “strengthening, to improve ones mental state, immunity, and overall sense of wellbeing.” If this unsupported poppycock is to be believed … and I don’t … then the vagus just might be the seat of the soul.

Meanwhile, it is true that emotional stress (frustration, aggravation, anger, anxiety, and grief) all can have effects on the vagus and vagal function. For example, stress can trigger acid reflux almost immediately; and the same goes for other symptoms, including a cardiac one, syncope (fainting).

There is also a new medical field that uses electronic vagal nerve stimulators, vagal stimulation, to treat recalcitrant epilepsy, depression, and some other neurological disorders. This post is not about improving vagal wellness with “vagal exercises,” and it isn’t about vagus nerve stimulation. As you will see, it is about what happens when the vagus nerves get sick or injured.

What Is the Vagus Nerve?

In the first year of medical school, the students take anatomy; and in my day, what determined whether you got an “A” or “B” was how well you knew the cranial nerves (CNs). By anatomic numbering, the vagus nerve is the tenth cranial nerve (CNX); and incidentally, and fittingly, the root word for vagus is vagabond or wanderer … and wander, it does.

The vagi (vagus plural) are the longest and most important nerves in the body with a profound array of functions, including control of phonatory (voice), gastrointestinal, visceral, neurological, cardiovascular, and respiratory functions. FYI: for the respiratory system, the vagus controls everything except the diaphragm, which has its own separate neural innervation from cervical (neck) nerve roots. The vagi are another underestimated, but important way in which the respiratory and digestive systems are joined.

Shown above is a top-to-bottom schematic of the vagi. You can see the main nerves coming out of the brain. The upper complex bushy/branching area is for the throat, esophagus, and airway; the lower bushy area is for the upper GI tract; and the bottom part (looking like a river delta) is for the viscera (internal organs), including the liver, pancreas, kidneys, and intestines.

The vagus nerves run from your head to your ass, and everywhere in between! The vagi have sensory, motor, and autonomic fibers. Sensory fibers convey to the brain what you feel, both consciously and unconsciously, and that includes (vagally-mediated) symptoms. Motor fibers make everything go/work, from voice and cough to esophagus, stomach, and visceral organs. Autonomic fibers make up the “automatic” nervous system, which controls unconscious functions like heart rate, blood pressure, swallowing, and digestion.

How the vagi are wired both outside and inside the brain is complex; and when it comes to nerve control centers, brainstem nuclei, the vagal nucleus is like Grand Central Station on steroids. Actually, it would be the size of the Pentagon, and that’s really big. The vagal nucleus is so large because it connects with so many other nerves and control centers within the brain.

Etiology of Vagal Neuropathy: Why Does It Go Bad?

After exiting the brain, the vagi course through the neck and then into the chest. Anywhere along their course, they are vulnerable to damage from infection, surgery, or trauma. Nerve damage is called neuropathy or neuropathies … from Latin: nervus- nerve and pathia suffering or damage. Thus, neuropathy means “sick-nerve” or “damaged nerve,” and the adjective, neurogenic, means “sick-nerve-caused.”

Vagal neuropathies can lead to problems such as pain and/or altered or impaired physiologic function; but what are its causes? Here are some etiology (“causal”) data from my lab:

Idiopathic/viral infection 40%

Head/neck/chest surgery 30%

Neurological disorders 8%

Head/neck/chest cancer 8%

Endotracheal intubation 8%

Trauma 6%

That head, neck, and chest surgery, cancer, infection and trauma can all interrupt or cause vagal nerve damage seems obvious. Cancer, surgery, or cancer surgery involving the skull base, thyroid gland, head and neck (vascular or spine), stomach, and esophagus especially put the vagi at risk. These causes and their relative risks are beyond the scope of the article; however, it seems evident that these nerves can be damaged anywhere along their paths.

The mysterious cause of vagal neuropathy is Endotracheal Intubation; the mechanism of nerve damage from this is unknown. In addition, there are no data that post-intubation vagal damage is the result of improper intubation, that is, when it happens, it is not due to some kind of malpractice event. In other words, we don’t understand the mechanism of this complication, but it is nobody’s fault.

In the medical literature, “idiopathic” (unknown cause) is considered the most common cause of cranial nerve, particularly vagal neuropathies. However, most clinicians never ask the question, “Did these symptoms start after an upper respiratory infection (URI)?” I do ask, and in my experience, at least half of patients who might otherwise fall into the idiopathic group have Post-Viral Vagal Neuropathies.

In 2001, I coined the term Post-Viral Vagal Neuropathy (PVVN) to describe a clinical entity that I saw often: Viral URIs leading to damage of the vagus nerve or nerves, resulting in a host of problems. With PVVN, symptoms may not be apparent immediately; often they begin days-to-weeks after the URI (e.g., cold, flu, sinusitis, bronchitis). Interestingly, Covid is a very uncommon cause of vagal neuropathy; however, it does often significantly worsen reflux in people who had some degree of reflux before.

Common Vagally-Mediated Neurogenic Symptoms

I know about the vagi because over the course of my career, I have seen about 25,000 patients with vagal neuropathies, which can be broadly lumped into five groups based on the symptom(s) and organ(s) of involvement: (1) phonatory (voice), (2) gastrointestinal, (3) neurological, (4) cardiovascular, and (5) respiratory symptoms; here are some examples:

Phonatory: Voice change, vocal fatigue, effortful phonation, loss of singing pitch-range

Gastrointestinal: First initiation of reflux, gastroparesis (bloating, nausea, vomiting)

Neurological: Chronic cough, odynophonia (painful speaking), sore/burning throat, atypical chest pain

Cardiovascular: Fainting (“physiological” and atypical vasovagal syncope), cardiac arrhythmias

Respiratory: Shortness of breath, asthma, pseudo-asthma, chronic cough, globus

References

Koufman J, Postma GN, Whang C, et al. Diagnostic laryngeal electromyography. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 124:603-606, 2001.

Amin MR, Koufman J. Vagal Neuropathy After Upper Respiratory Infection: A Viral Etiology?

Am J Otolaryngol 22:251-256, 2001.