At-A-Glance

- Dr. Jamie Koufman is an American physician and scientist whose research in laryngology and acid reflux has led to discoveries that have impacted two generations of physicians and patients.

- Dr. Koufman’s pioneering work put Respiratory Reflux (aka LPR) on the map, and her book Dropping Acid was the first to link the words: Reflux, Diet, and Cure. She also coined the terms Laryngopharyngeal Reflux, Airway Reflux, Silent Reflux, and Respiratory Reflux.

- Dr. Koufman has studied the diagnosis, clinical manifestations, treatment options, and cell biology of reflux … including the biology of Pepsin, the primary stomach enzyme that causes reflux inflammation and tissue damage in the respiratory tract and esophagus.

- This post is personal and excerpted from the introduction, Connecting The Dots, to my forthcoming book, Respiratory Reflux: How Silent Reflux Causes Diseases.

- It is revealing that my alternative titles were, “The History of Respiratory Reflux” and “Silent Reflux: A Memoire.

Join Facebook Live with Dr. Jamie Koufman the 1st Wednesday of the Month at Noon EDST; and if You Have Questions About Respiratory Reflux Ask Them There. If You Miss It Live, It Gets Posted to YouTube Afterwards. NB: The May 1, 2024 topic is Chronic Cough.

I celebrate the ideas, discoveries, and experiences I’ve had over the course of what has been an exciting and rewarding career. My insight into Respiratory Reflux (RR) is a result of the path I’ve followed, with each discovery leading me one step further until I arrived where I am today. Having treated at least one hundred thousand patients with RR, I must admit that my patients have taught me much of what I know.

General or Laser Surgery?

My role model was my Uncle Clint. He was a surgeon and his patients adored him. I started making rounds with him when I was 10. He taught me that the needs of the patient always come first. So, when I went to the Boston University School of Medicine (his alma mater) in 1969, I wanted to be a general surgeon like him.

In my third year, I rotated in otolaryngology—head and Neck Surgery (ENT), which ended up changing my goal of being a general surgeon. During that rotation, I discovered that the department chief, Dr. M. Stuart Strong, was pioneering endoscopic microlaryngeal laser surgery. (Endoscopic means through the mouth with a special hollow viewing tube, and microlaryngeal means performed on the larynx or vocal cords while looking through a microscope, and with a surgical laser, the very first, a prototype.)

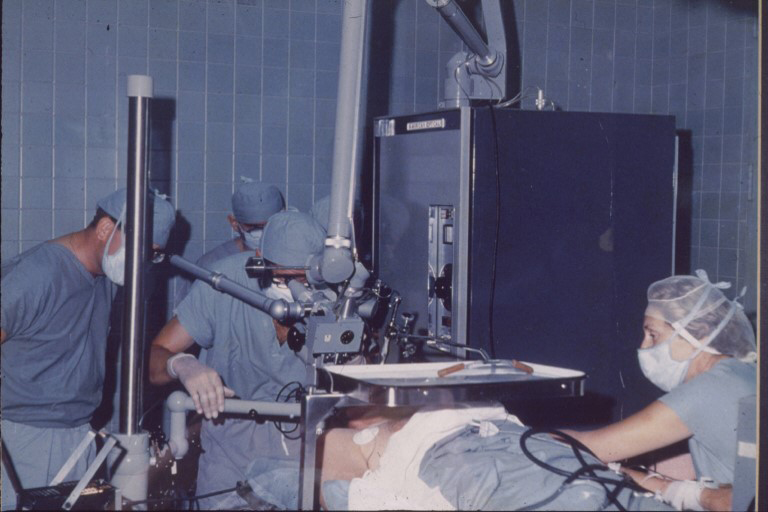

This shows Dr. M. Stuart Strong using the first (experimental) carbon-dioxide (CO2) laser to remove a growth. Dr. Strong is front and center, operating while through the microscope.

A huge TV monitor in the OR showed the surgical field. Imagine my awe and excitement at the sight of the vocal cords projected on the giant screen; watching as a tiny vocal cord wart, with the push of a foot pedal and a click, was vaporized like magic, gone!

That was all I needed to see. I wanted to be a laryngologist—not just a laryngologist but a laryngeal laser surgeon. A laryngologist is a subspecialized otolaryngologist (ENT) focused on Laryngology and the Voice.

I spent as much time as possible watching and learning from Dr. Strong in his office, assisting, and soon performing microlaryngeal laser surgery cases. I wanted to be at the cutting edge of this amazing new field of medicine… it was thrilling. I wanted to pioneer and advance technology and state-of-the-art.

Wake Forest University School of Medicine

I did not go into private practice; I was to be one of the first Academic laryngologists in the world. In 1978, I joined the Department of Otolaryngology of the Wake Forest University School of Medicine. The administration was very generous, allowing me to purchase all of the best equipment in the world for myself and my surgical team. Soon, I had the first (not-experimental) carbon-dioxide laser in the world.

I was quickly flooded with patients with all kinds of airway obstruction, many of whom had laryngeal warts (Recurrent Respiratory Papillomas). Sometimes, I did as many as 17-20 cases a day. And because I was the first prolific laser surgeon, I was invited to lecture all over the country. After each lecture, as I left the podium, my parting shot was, “Just send me the patients that you don’t want or don’t know what to do with.” Within three years, I had a national practice.

I remained focused on breaking new ground: I organized the first Institutional Laser and Safety and Utilization Committee, had the first Fellowship in Laryngology, and introduced the next wavelength laser into medical practice, the Nd: YAG laser, which I used to clear the airway, including the trachea and bronchi due to obstructing benign and malignant tumors.

At this point, I will leave my career as a laryngeal surgeon to focus on acid reflux; if you are interested in my other contributions to laryngology, please look at my Curriculum vitae. That said, I need to emphasize that I specifically chose laryngology because the specialty was new and waiting to be explored.

Baptism By Reflux

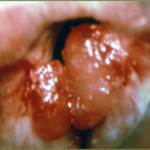

In 1981, a dramatic case served as my initiation to acid reflux in the larynx. I was emergently consulted to see a hospital patient with extreme airway obstruction. I rushed to the bedside of a woman gasping for air like a fish out of water. She pointed to her throat and wheezed, “Can’t breathe… acid reflux.” I examined her with a portable scope and observed that she had diffuse inflammation and two large, obstructing granulomas, shown below.

I asked her nurse to call the operating room STAT and tell them I was on my way, and I wheeled the patient down to the OR. Within a few moments—poof! With a few taps of my foot and flashes of the laser, I had the granulomas gone and her airway back to normal.

Over time, I examined many other patients with the same pattern of diffuse inflammation (with or without granulomas) that I had seen in the woman who couldn’t breathe. This pattern of swelling appeared to be consistent with reflux, but many of the patients did not have heartburn or indigestion—that is, no GERD.

Pinching pH-Monitoring

I’d heard that the gastrointestinal specialists (GIs), aka gastroenterologists, had a device that enabled a diagnostic procedure known as ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring (pH-metry). Here’s how it worked: the patient had a thin, soft tube inserted into their nose and down into the esophagus. In this tube, or probe was a pH (acid) sensor, and while it was left inside the patient for twenty-four hours, the pH (acidity) in the esophagus was recorded in real-time by a minicomputer housed in a small pouch that the patient wore on a strap around the waist.

In 1983, I was invited to attend a monthly GI research meeting to present my findings and case for “reflux laryngitis.” To my surprise, after finishing my presentation, The Big Cheese, a well-respected chair of the GI department, stood up and told me that acid reflux does not occur in the throat and that there was no such thing as reflux laryngitis.

Immediately after my presentation’s disappointing outcome, I went to the GI fellows’ room. I stood in the middle of the room and yelled, “Who wants to be famous?” Dr. Gregory Weiner raised his hand and said, “I do.” I made him agree not to tell the GI chair about what we were up to until we had some data … but I wanted to prove that there was acid reflux in many of my patients’ throats.

To test my patients, we used two separate pH-metry set-ups—one in the esophagus and the other in the pharynx (throat). Eureka! Most patients with clinical reflux laryngitis showed reflux in the pharyngeal pH probe. I was right.

Soon, Dr. Castell and the other GIs knew what we were doing, and within a year, I had proved that acid reflux could indeed come up into the throat and cause disease. In 1986, we published a seminal abstract in a GI journal: “Is hoarseness an atypical manifestation of gastroesophageal reflux? An ambulatory 24-hour pH study.” Thereafter, some other similar reports were published again in the GI literature, and incidentally, I was never the first author of any of those papers.

I was pleased to see my hypothesis validated, but I wasn’t satisfied to only publish in GI journals; after all, I (“we”) had proven the existence of reflux into the throat, so I wanted to publish the findings in my field of otolaryngology. In 1988, then, as the first author, I published a report entitled “Reflux laryngitis and its sequelae: The diagnostic role of ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring” in the Journal of Voice. This event marked a major turning point in my career and in the history of respiratory reflux.

As long as we had been publishing my data in their journals, and with their names as the first authors, GIs were willing to entertain the concept of throat reflux, which they insisted on calling atypical reflux. However, as soon as I made it clear that I was serious about pursuing this research within otolaryngology, their position appeared to shift. After all, what I was proposing would not only challenge fundamental assumptions of their field, but it would also threaten the GI business model — “Reflux is heartburn; heartburn is reflux; it’s esophageal and we own it”—that allowed them to make money hand over fist from the mid-1970s to the present) just by doing endoscopies.

There was more at stake than whether reflux into the throat was possible. Proving it was one thing, but reckoning that with its implications in the real world of medical practice was another entirely. Essentially, the GI “heartburn business model” might be made redundant. The GIs started circling the wagons early.

Comments: (1) To this day, the GIs have not embraced respiratory reflux (RR) as a real thing, and actually, they have been adversarial since I began doing my own reflux testing and publishing the results. Many GIs still pretend that there is no such thing as RR. (2) GIs have made billions and billions of additional dollars by owning ASCs (ambulatory surgical centers) that reap the highly lucrative facility fees for procedures they perform. (3) Although the GIs are the “go-to” doctors for acid reflux, they have no diagnostic tests or treatments for RR; they remain clueless. (4) GIs have unfairly squashed competition from newer, superior, office-based diagnostics—see TNE— by manipulating Medicare reimbursement. (5) The Expensive and reckless GI “heartburn business model” focused only on the esophagus has to go—for every person with GI esophageal disease, there are 4-5 with silent RR.

Better Reflux Testing Technology

In 1987, I set up my own reflux testing laboratory that included a double-probe pH-metry system and an esophageal manometry system to help with the accurate placement of the pH probes. Obviously, I was most interested in the reflux pH data from the pharyngeal (throat) probe.

The company that manufactured the GI reflux-testing equipment worked with me to develop new pH probes and monitoring systems, which had both the pharyngeal sensor and the esophageal sensor embedded in the same catheter, and one box (minicomputer) to collect the data.

Thus was born ambulatory 24-hour double-probe (simultaneous pharyngeal and esophageal) pH-monitoring – a mouthful, to be sure. For thirty-five years, I used the best diagnostic equipment in the world. I accumulated double-probe pH-monitoring data on tens of thousands of patients. No one else has ever had reflux-testing technology of this type, and my data form the backbone of my clinical experience … clinical data plus pH-metry equals the truth about RR.

Today, no one is doing quality reflux testing for RR because Medicare reimbursement is so low. It is only worth it if you are a GI who owns an ASC and can get both the professional and facility fees. GIs have set up the system so that they cannot have competition because other physician specialties are office-based; thus, there is no lucrative facility fee to be had.

Laryngopharyngeal Reflux (LPR)

I was particularly focused on treating and studying patients with reflux-caused cancer of the larynx, subglottic stenosis (airway scarring), reflux laryngitis, globus (lump-in-the-throat sensation), and dysphagia (difficulty swallowing). Research with my new technology continued to corroborate my earlier findings that pharyngeal reflux was the underlying problem in all of those conditions.

Meanwhile, fewer than 20% of my patients ever had esophageal symptoms, i.e., heartburn and indigestion. Therefore, since my patients didn’t have GERD, I felt that a new diagnostic term was needed. And in 1987, I coined the term Laryngopharyngeal Reflux (LPR), literally defined as “backflow into the larynx (voice box) and pharynx (throat).”

Silent Reflux

You may be interested in knowing how the term silent reflux came to be. It was coined by my friend and patient, Dr. Walter Bo, chair of the Wake Forest anatomy department. In 1988, Walter came to see me as a patient because he was experiencing several symptoms of LPR, including severe hoarseness.

After his examination, I told him that he had acid reflux. He laughed and dismissed this diagnosis because he thought reflux was heartburn and didn’t have any of that. After I explained how one could have reflux without heartburn, Dr. Bo rolled his eyes and then proclaimed, “I see – I have the silent kind of reflux.” I responded, “Yes, that’s it, Walter. You have silent reflux.”

Discovering About Pepsin

I needed to know more about reflux, so I searched the medical literature and consulted European colleagues doing basic science research on the mechanism of swelling, inflammation, and even carcinogenesis of acid reflux; both the literature and colleagues pointed in one direction, Pepin the primary digestive enzyme in the stomach.

It is pepsin (not acid) that causes tissue damage, so at that time I thought we should call acid reflux “peptic reflux.” But there was a quirk in the pepsin story: pepsin needs some acid for its activation. For the next four decades, I would study pepsin.

For some forty years, my research focused on studying acid and pepsin. I already knew that pepsin was a powerful proteolytic enzyme—that is, that it breaks down proteins; in fact, it’s so potent that when biochemists study large proteins, their first step is often something called pepsinization, a process that uses pig pepsin to break down large proteins into smaller bits for study. In 1987, I crafted a five-year reflux research plan (about half bench science), which took me 20 years to complete.

End of Part I: Who Is Dr. Jamie Koufman Respiratory Reflux Expert?

Click Here For Part II

Please subscribe to this blog to stay current; if you would like to schedule a virtual consultation with me, you can Book It Online.