At-A-Glance

- Chronic cough (four weeks or more) is one of the most commons reasons why people seek medical attention, and most are non-smokers with normal chest x-rays, that is, with no lung disease. Because the lungs are uninvolved, this type of cough is called Non-Pulmonary.

- The most common cause of non-pulmonary cough is Respiratory Reflux, aka LPR (85%), and the second, Neurogenic Cough (35%). Obviously there is overlap as most people with neurogenic cough also have reflux. Only 10% of people with chronic cough have neurogenic cough alone, without reflux.

- People with neurogenic cough have dry cough throughout the day, but not at night; and coughing may be triggered by: (1) fumes (e.g., auto exhaust, perfume, burnt toast), (2) temperature change (e.g., air conditioning), and (3) speaking, laughing or talking on the telephone. Reflux-related cough is different, characterized by: (1) coughing after meals, (2) awakening in the middle of the night with violent coughing, (3) coughing after bending over, and (4) sometimes, choking episodes. NB: Neurogenic cough is almost always “dry,” non-productive; whereas reflux-related cough is usually “wet,” phlegmy.

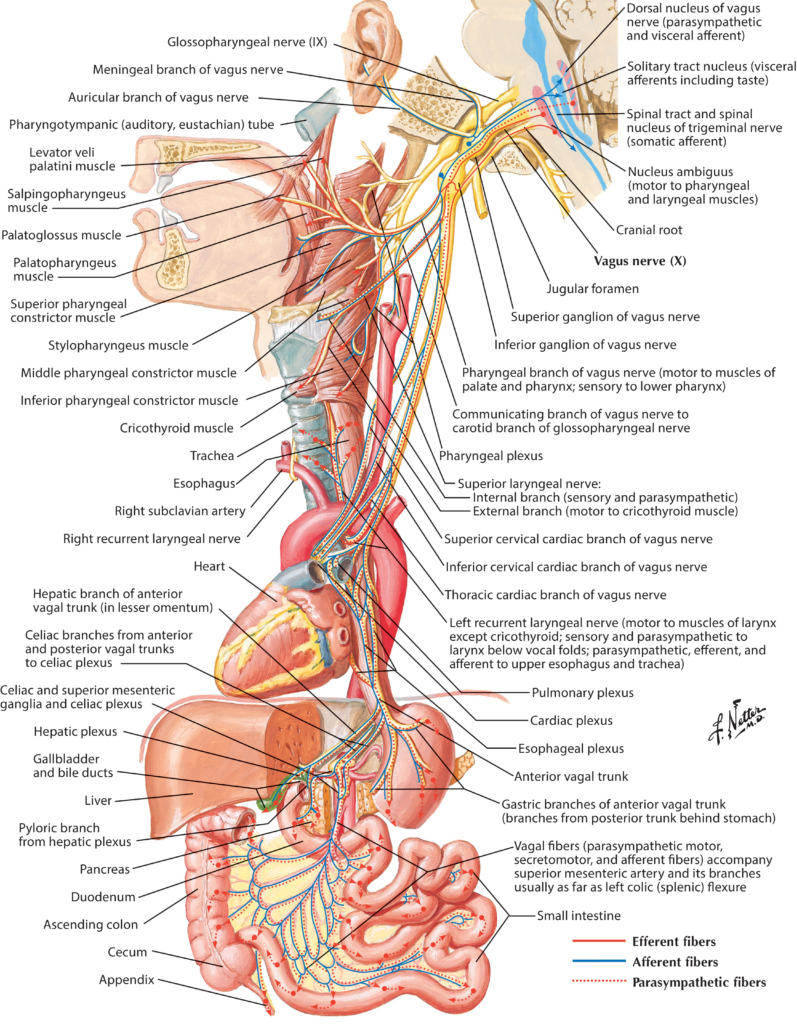

- The vagus nerve is the tenth cranial (coming out of the brain) nerve and it is one of the longest and most important nerves in the body. The vagi (plural of vagus) control virtually every respiratory and digestive function.

- Viral upper respiratory infections can damage the vagus nerves as they reside just under the lining membranes of the throat; and post-Viral Vagal Neuropathy, a resulting Sick Nerve Syndrome is the most common cause of neurogenic cough.

- In my experience, effective treatment (cure) of neurogenic cough requires use of medicines that stabilize nerve function, namely, amitriptyline (Elavil) and gabapentin (Neurontin).

Chronic (> 4 weeks) cough is one of the most common reasons that people seek attention; however, it is one of the most commonly misdiagnosed and mismanaged medical conditions. But before going further, take notice that the symptom “cough” should be differentiated from “chronic throat-clearing” due to post nasal drip, a symptom of LPR reflux. Obviously, a person can have both types of symptoms from respiratory reflux (aka LPR) with or without a neurogenic component.

The focus of this post is neurogenic cough, the second most common cause of chronic cough; but do remember that most people with it also have reflux. In addition, The relationship between reflux-related and neurogenic cough is interactive, as reflux can make neurogenic cough much worse … to the point that for many people who have both, effective anti-reflux treatment may be all that is needed to stop the cough. Only about 10% of people with non-pulmonary chronic cough have neurogenic cough exclusively.

How Do I Know if I Have Neurogenic Cough? What Are Its Symptoms?

Is your cough dry, that is, nonproductive?

Does change of temperature make you cough?

Does laughing or chuckling cause you to cough?

Do you cough throughout the day, but never during sleep?

Does speaking, singing, or talking on the phone cause you to cough?

Do fumes (e.g., perfume, automobile exhaust, burnt toast) cause you to cough?

If the answer to any of these questions is YES, you may have neurogenic cough.

Fill out the Koufman Chronic Cough Index below; add the “yeses” in each column, and that will give you the “reflux-to-neurogenic” ratio, that is, a presumptive diagnosis. The “yeses” in the left column are for reflux-related cough symptoms; and the “yeses” in the right column are for neurogenic cough symptoms. If all your yeses are on the left, you have reflux-related cough; if all your yeses are on the right, you have neurogenic cough. And obviously, if you have “yeses” in both columns, you have both reflux-related and neurogenic cough.

Now, add the YESES in the two columns up to derive the Reflux-to-Neurogenic ratio. Although this index is simple, it seems to work as a diagnostic instrument; for more about this, see my book, The Chronic Cough Enigma.

What is the Vagus Nerve and What Does It Do?

There are twelve cranial nerves that medical students study for two weeks, because the cranial nerves are important. (“Cranial” means that these nerves that come out if the brain.) Most of the 12 nerves account for our senses (e.g., vision, smell, taste, hearing, balance), but the tenth cranial nerve, the vagus nerve, is different.

The word, vagus, is derived from the word wanderer or vagabond, and indeed, the vagi (plural of vagus) are among the longest nerves in the body and they control virtually the entire respiratory and digestive systems. That’s right; one nerve controls respiratory and digestive functions. (Technically, it is all functions with the exception of the diaphragm, which has its own separate neural innervation.) Also, the vagi influence heart rate and cardiac function. Indeed, the vagus nerves are vital to your survival; if you were to cut both them, you would die.

Vagal symptoms include nausea, bloating, heartburn, hoarseness, cough, shortness of breath, choking, and asthma, just to name a few. And when it comes to cough, the vagus accounts for the feeling that a cough is needed, as well as the act of coughing itself. The vagi are sensory and motor nerves as well as autonomic (“automatic”) nerves, which control swallowing, digestion, heart rate, etc.

When someone faints … have you ever heard the expression they went vagal? The vagus can cause bradycardia (slowing down the heart rate). Indeed, the vagi are well-connected to emotions, and with this type of fainting, it is emotions that cause the bradycardia; it’s a slowing-down-of-the-heart type of fainting.

If you examine the picture above — everything you see is controlled by the vagi — it is easy to see why the vagi are so important. But here’s the rub: although the vagi are among the most important nerves in the body, most doctors know almost nothing about them! Even neurologists, nerve doctors, appear to know little about the vagus nerves.

Bottom Line: The respiratory and digestive tracts are part of one unified system and the “operating system,” the vagi are the driving neural network for every function and symptom … for example, neurogenic cough. (BTW, the respiratory and digestive tracts are also directly connected in the throat.)

The vagus nerves remain a “black hole” in the curriculum of medical schools and residency training programs; but with 45-years experience working in the field, in a relative sense I am an “expert.” But as much as I may know about vagal function and the diseases that affect them, I grant you that I am a still-learning pioneer, with only a modicum of knowledge.

Important Information: The June before Covid, I gave the Keynote Lecture at an event at the Boston University School of Medicine, and in my opinion, it, The New Field of Integrated Aerodigestive Medicine, represents my most important contribution to the future of U.S. healthcare. In it, I explain how the respiratory system is linked to the digestive system, and how clinicians should approach the diagnosis and treatment of respiratory diseases and vagally-mediated problems.

What Is Neuropathy? What Is Post-Viral Vagal Neuropathy?

The vagus nerves can be damaged or injured a number of different ways, any of which may lead to the development of neurogenic cough or other vagally-mediated neurogenic symptoms. (While not the specific topic of this post, it is worth mentioning that voice-use pain, vocal fatigue, sore throat and throat burn are also vagally-mediated neurogenic symptoms.) The word neuropathy means “sick nerve,” and the word neurogenic means “sick-nerve-caused.” Thus, vagal neuropathies are the result of diseases or events that damage or impair those nerves in some way.

The most common cause of vagal neuropathy is a viral upper respiratory infection (URI). Anatomically, the vagi come out of the brain and track along the front of the spine. In the throat, the vagi live just under the lining membranes, and this makes them susceptible to damage from some infections.

When a patient has neurogenic cough, more than half of the time, they will date the onset to an infection (e.g. URI, sinusitis, bronchitis); but even when there is no history of a no clear-cut precipitating infection, the clinical pattern is still usually compatible with Post-Viral Vagal Neuropathy.

For such patients, the examinations that are performed by someone like me, include neuro-diagnostic testing called Laryngeal Electromyography (LEMG) to confirm the diagnosis of Vocal Cord Paresis, or partial vocal cord paralysis. (Vocal cord paresis and viral vagal neuropathies appear to be common. Many years ago, I studied 40 “normal” subjects using LEMG, and to my surprise, 45% (18/40) of the subjects had vagal neuropathies.)

Even if you do not have a memory of having had an infection prior to development of your neurogenic cough, I still believe that viral infections are main cause of such neuropathies. And just for completeness here, the other causes of vagal injuries are head and neck (e.g., thyroid) surgery, intubation for a general anesthetic, neck trauma, and neurologic disorders; again for more on this, see my LEMG article.

What’s the Treatment for Neurogenic Cough?

Disclaimer: The information below reflects the author’s clinical experience; it is not offered not as medical advice; and it should not replace any recommendation(s) or treatment(s) prescribed by your physician(s); use of this information is solely at the risk and responsibility of the reader/user. Jamie Koufman, M.D.

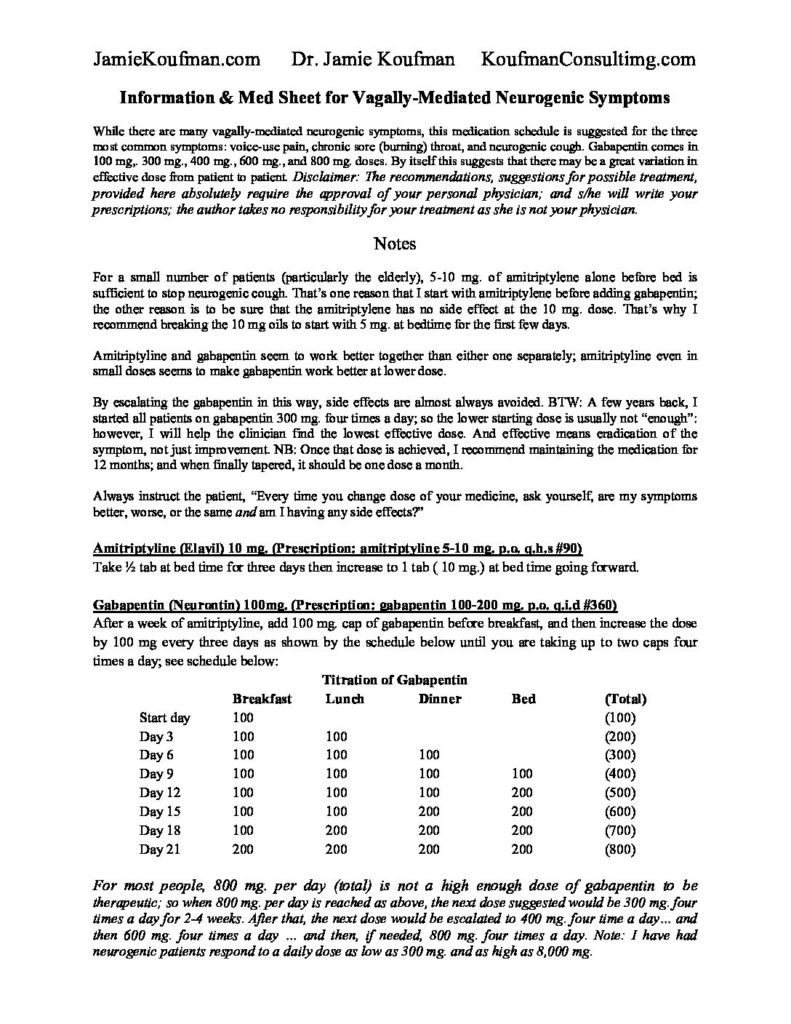

Medical treatment of neurogenic cough is not always necessary; if the patient has concomitant reflux, anti-reflux treatment should come first. For the (reflux-controlled) patient with persistent, recalcitrant, neurogenic cough, then “neurogenic” medication(s) are indicated. The key is to titrate the medication and doses for each individual, using the smallest effective dose. In order to do that, very small doses of medication are initially employed and then increased incrementally until the cough is gone … not just improved. Thereafter, most patients need a minimum of 6-12 months of medical treatment to facilitate a “reset” in the brainstem. In other words, the medication should not be stopped immediately when the cough is gone; discontinuance too soon may result in subsequent return of the neurogenic cough.

Initially, amitriptyline is used in small doses before bed. While this is traditionally used as an antidepressant, Elavil 10 mg. is not enough to make a fly happy; it is being used in this case for treatment of neurogenic cough. At this dose, side-effects are very uncommon; although the amitriptyline may help patients sleep.

When gabapentin is added, again, it is in small doses that can be escalated every few (3) days. The patient must be instructed, “Every time you change the dose, ask yourself if the cough better and if you are you having and side effects?” The protocol for gabapentin is shown in the table below.

Amitriptyline (Elavil) 10mg.: This will require your doctor to write a prescription*

These small pills may be difficult to break in half; however, take ½ tab (5 mg.) at bed time for 3-4 days; then if no side-effects, increase to 1 tab (10 mg.) at bed time going forward. Amitriptyline 10 mg. alone will stop neurogenic cough in 15% of people; most people need the combination of amitriptyline and gabapentin. Amitriptyline makes the gabapentin work better and the gabapentin makes the amitriptyline work better; their effects are synergistic in a beneficial way. * Amitriptyline (Elavil) 5-10 mg. QHS, #30 … note: the generic will do fine

Gabapentin (Neurontin) 100-800 mg.: This will require your doctor to write a prescription*

After you have been on the amitriptyline for a week, if you still have a neurogenic cough, start taking gabapentin 100 mg. (one cap) in the morning before breakfast. Every three days, you can increase the dose (see schedule below) until you are taking two caps at breakfast, lunch, dinner and bedtime, a total of 800 mg. * Gabapentin (Neurontin) 100-200 mg. QID, #240 … note: the generic will do fine. PRINT PDF.

PRINT PDF. For most people with neurogenic cough, 800 mg. of gabapentin is not quite enough to knock out the cough. If you are on gabapentin 800 mg. (with 10 mg of amitriptyline) with insufficient benefit and no ill effects, contact your physician and escalate to gabapentin 300 mg. QID (4x/day) … if more is needed after that, perhaps escalate to gabapentin 400 mg. QID. This protocol is effective for 75% of patients … good luck!

Other vagally-mediated neurogenic (nerve-caused) symptoms that may be related to vagal neuropathy are: voice use pain, vocal fatigue, chronic sore throat, and throat-burn. While those latter symptoms can be seen with reflux, or worsened by reflux, they are all primarily neurogenic symptoms. I include this paragraph for readers who may suffer from any of the above, because treatment of vagally mediated symptoms, not just neurogenic cough, in my experience follows the medication schedule above.

Finally, in a prior blog, I have discussed Reflux-Related Non-Pulmonary Chronic Cough; you should look at that blog along with this one.