The VAGUS Nerve Part III: Vagally-Mediated Syndromes Affecting the Gastrointestinal, Respiratory, and Cardiovascular Systems

At-A-Glance

- This is the third installment in a three-part article on the vagus nerve; this one covers the consequences of vagal neuropathies affecting the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems.

- If you haven’t already done so, I recommend that you read The Vagus: Part I, and perhaps Part II, especially if you have chronic problems with your voice.

- This post is about vagal neuropathies that can cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as heartburn, nausea, and vomiting; respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath and chronic cough; and cardiovascular symptoms such as fainting and irregular heartbeat.

Dear Reader: Until now, there has been a paucity of information about the vagus nerve and vagally-mediated neuropathic syndromes. This topic is impactful and this blog is expansive; therefore, I have divided it into three parts. This is Part III, and the three parts taken together are my “White Paper on the Vagus Nerve”… rather like a medical tell-all from an experienced physician. Prego! Most of what I know is here, including clinical observations that have not been previously published. -Dr. Jamie Koufman

This is Part III in a three-part series of articles on the vagus nerve. Part I covered the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the vagus, as well as the protean manifestations of vagal neuropathies. Part II specifically covered the phonatory (voice) and neurological (pain) sequelae.

This final section covers vagal neuropathies that affect the gastrointestinal (GI), respiratory, and cardiovascular systems. Vagal neuropathies affecting these systems are less common than the phonatory and neurological ones, covered in the last post. Discussed here …

GI symptoms: Early-satiety, bloating, nausea, vomiting, and sudden-onset acid reflux

Respiratory symptoms: Shortness of breath, chronic cough, and neurogenic asthma

Cardiovascular symptoms: Vasovagal syncope (fainting) and cardiac arrhythmias (irregular heartbeat)

It’s PVVN Again: It is my belief that most vagal neuropathies (“sick-nerve syndromes”) are the result of viral upper respiratory infections (URIs) that probably infect and damage the vagus nerves in the neck, Post-Viral Vagal Neuropathy (PVVN). Even patients who don’t remember having had a URI may still have a PVVN clinical pattern based on symptoms, examination, and laryngeal electromyography.

GASTROINTESTINAL (GI) SEQUELAE OF VAGAL NEUROPATHIES

This section will focus on two topics: gastroparesis and the sudden-onset reflux; these both may follow a precipitating event such as stomach surgery or PVVN and, they often go together, gastroparesis and reflux.

What Is Gastroparesis?

Gastroparesis ― literally stomach partial paralysis ― is a motility problem that negatively impacts the ability of the muscles of the stomach to contract, slowing stomach emptying, which normally propels gastric contents forward into the digestive tract. Gastroparesis is a relatively uncommon manifestation of vagal neuromuscular dysfunction.

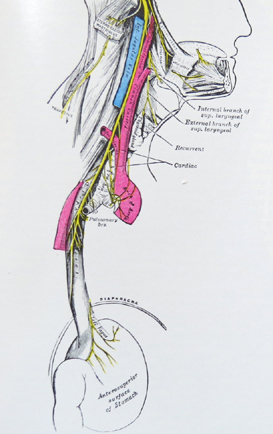

This drawing shows that vagal nerves come off the esophagus and innervate the stomach

Gastroparesis is characterized by delayed gastric emptying, and its typical symptoms are early-satiety, bloating, nausea, vomiting, belching, and acid reflux. Its reported causes are diabetes, Parkinsonism, post-surgical, idiopathic, and post-viral.

I do not consider myself an expert on gastroparesis, because most patients with gastroparesis symptoms will go to a GI doctor. That said, I have seen many patients with it, and among them there is a big subgroup with both gastroparesis and reflux, usually due to PVVN. Gastroparesis is usually a “chronic-intermittent” problem, and though infrequent, the attacks can send the sufferer to the hospital.

Illustrative Case Example: Intermittent Bouts of Severe Nausea and Vomiting

A 34-year-old nursing assistant came to me with a two-year history of relatively- infrequent attacks of severe nausea and vomiting. These attacks occurred every few months, usually on awakening in the morning. Once an attack began, he would grab a bucket and hightail it to the emergency room, because the symptoms were relentless. At the hospital, they would treat him with sedation, antiemetics, and with intravenous support.

His gastroenterologist had tried him on metoclopramide (Reglan) without benefit. The patient came to see me, desperate but hopeful. He had come across my paper on PVVN; and since his first attack followed a severe URI, he thought that he might have PVVN … pretty smart guy … he was right. BTW, he had respiratory reflux symptoms, but no heartburn or indigestion. Interestingly, the patient had figured out that “hot” food items containing capsaicin, especially green bell peppers seemed to trigger attacks, so he avoided those items.

On examination, he had moderately-severe reflux and bilateral vocal cord paresis (partial paralysis) (VCP). The PVVN diagnosis was confirmed by the classic pattern on laryngeal electromyography (LEMG). FYI: With PVVN, all four branches of the vagi tested typically show decreased recruitment with polyphasic motor units.

I treated him with gabapentin, escalating the dose to 1,600 mg. per day. A year later, he still had not reported any attacks, and at that point, I reduced his gabapentin to 800 mg. at bedtime. It has been years now with no attacks, so we could probably taper off the medicine now.

Comment: I believe that gastroparesis may be more common that we know. Personally, I do not bother ordering gastric emptying studies, because in many cases the problem is inconsistent, that is, intermittent, so the test may be falsely negative. For me, it is a clinical diagnosis.

Gastroparesis is often associated with reflux, and sometimes with trigger foods precipitating attacks. In the case above, the trigger was capsaicin, the active ingredient that gives the “hot” to hot chili peppers, cayenne pepper, bell peppers, and jalapenos. The hotter the pepper, the more capsaicin it contains. The above patient knew that he needed to avoid foods with capsaicin in them.

A warning about stomach surgery: The vagi can be injured during stomach surgery, especially lap-band surgery for obesity. The Cleveland Clinic states that as many as 50% of lab-band patients have complications. Indeed, I have seen many such patients with post-surgical gastroparesis and/or severe reflux.

Comment: Throughout this series on the vagus, I have consistently used gabapentin (with or without a small dose of amitriptyline) as my primary therapeutic agent(s). It seems that the gabapentin-like drugs work well on sick vagi. BTW, the newer pregabalin with the trade name Lyrica is no better than gabapentin, and it’s more expensive and harder to titrate.

What About The Viscera? Food For Thought

Remember this post is about vagal neuropathies in my field; however, I hope that this post will catalyze interest in the potential downstream effects of “high” vagal disruption (most likely in the neck). After all, what do we know about the effects of vagal neuropathies on the viscera, i.e., liver, gall bladder, pancreas, kidneys, and intestines? Anything?

Can Vagal Neuropathy Cause Reflux?

PVVN sudden-onset neuropathy can cause sudden-onset reflux as the entire GI system is vagally mediated. Absolutely, reflux can occur for the first time as a result of PVVN. It is important to stress that symptoms often overlap organ systems. Indeed, combined symptoms (such as reflux and gastroparesis) are the rule rather than the exception, especially when it comes to the respiratory and digestive symptoms.

The respiratory tract is the aero- in the term Aerodigestive, and the two parts of the aerodigestive tract are intimately interconnected anatomically (with the vocal cords often being the divider between the two systems) and neurologically, with a singular control system, the vagus.

I think that my legacy will be Integrated Aerodigestive Medicine (IAM). In a future post, I will further define IAM and suggest that it should be a primary care field, and try to keep the expensive specialists out of it. In addition, I will offer an outline of the new IAM curriculum. IAM could radically transform ― better and less expensive care ― day-to-day healthcare for everyone.

In the case below, again, symptoms do overlap organ systems; they are primarily gastrointestinal (reflux), with phonatory and respiratory symptoms, plus neurogenic cough.

Illustrative Case Example: PVVN with Reflux, Dysphonia, and Cough

A 39-year-old, previously-healthy attorney presented with hoarseness, cough, and acid reflux two months after he had had an URI. He reported that he had been quite sick with a flu-like illness. Three days after the onset, he lost his voice and he began to cough non-stop. He also had excessive mucus, difficulty swallowing, and heartburn. He reported that he could taste “bitter reflux” when he awoke in the morning.

A few days later, he went to see an ENT doctor who found that he had reflux, and that the left vocal cord was paralyzed. The doctor tried to put the patient on Dexilant and send him to a speech-language therapist … both of which the patient declined. A few weeks later, he came to see me. He did have vocal cord paresis and severe respiratory reflux with a PVVN LEMG pattern. The cough was both reflux-caused and neurogenic based on symptoms and testing.

He was treated for reflux and neurogenic cough, and over the next two months, his symptoms resolved, but repeat examination showed that he still had reduced movement of the left vocal cord. At that point, I sent him for voice therapy, and over time his voice improved as he developed adaptive compensatory laryngeal biomechanics; vocal cord closure was achieved as the good side strengthened.

Comment: This patient never had reflux, never had a cough, and never had a voice problem until his URI. In this PVVN case, it must be assumed that the neuropathies caused decompensation of the whole reflux prevention system, as well as cause the cough and paresis. The take-away is simply that PVVN can disrupt more than one system; and treating each component, i.e., reflux and neurogenic cough treatment, is effective, even if the vagi never fully recover. This last point is important, namely, that for most people, having a vagal neuropathy does not necessarily lead to long-term or permanent problems.

RESPIRATORY SEQUELAE OF VAGAL NEUROPATHIES

This section is about shortness of breath, asthma, and neurogenic cough.

Shortness Of Breath: Difficulty Taking A Full Breath In

With clear chest X-rays, no lung disease, no asthma or airway obstruction, and normal pulmonary function tests, approximately 25% of respiratory reflux patients have shortness of breath.

But it’s a very particular and peculiar type of shortness of breath, not at all like getting shortness of breath from climbing a lot of stairs or aerobic exercise. Do you have difficulty taking a full breath in? I ask … and the response is YES.

This symptom is so specific that it’s almost pathognomonic for respiratory reflux (LPR) and vagal neuropathy. That’s because with normal lungs and airway, this symptom cannot be due to the respiratory reflux itself; it has to be vagally mediated. Sure enough, when the records of patients with this symptom are scrutinized, virtually all have vocal cord paresis and LEMG-proven vagal neuropathies, in addition to having respiratory reflux.

Illustrative Case Example: A 20-something woman with a two-year history of shortness of breath came to me for evaluation and treatment. When she returned for her first follow-up visit three weeks later, she reported, My shortness of breath went away after I slept sitting up in a chair for five days!

Comment: I think that this case suggests that respiratory reflux influences (and is influenced by) a dysfunctional vagal system; this brand of shortness of breath is vagal, but at the same time somehow reflux-related. I just cannot explain this other than to express the enigmatic thought that vagal function and dysfunction influences vagal function and dysfunction in mysterious ways.

Neurogenic Cough

I have already written a blog about Neurogenic Cough, so let me express here some key clinical differentiating points. But before discussing how neurogenic- differs from reflux-related cough, let me remind you of the distribution of coughers from a 2012 study†: 40% had reflux-related cough alone; 14% had neurogenic cough alone; and 46% had both. Thus, neurogenic coughers make as many as 60%.

So, how can the clinician know how to treat? In general, a wet, productive cough is associated with reflux; while a dry cough is typically neurogenic. Again remember that many patients have both; thus both, a wet and a dry cough.

With reflux, the tell-tale symptoms are coughing after eating, after lying down, when bending over, and most certainly, when awaking from sleep coughing; and it’s often violent coughing, sometimes associated with difficulty breathing, gasping air like a fish out of water, trouble getting air IN (laryngospasm).

On the other hand, typically, neurogenic cough is triggered by change of temperature, e.g., going into air conditioning, coughing with talking, chuckling, singing, and with fumes, e.g., perfume, bread toasting, automobile exhaust. Finally, exclusively neurogenic coughers (dry) cough all day long, every day, but never at night.

Neurogenic Asthma?

One of the most common triggers for true asthma is respiratory reflux (77%); however, in patients who also have vagal neuropathies, the asthma attacks can be more-easily triggered by, for example, just by coughing, eating spicy, peppery foods (foods with capsaicin), and by fumes.

While fumes can always trigger asthma without a vagal neuropathy, it appears that “the asthma-trigger-response” is overly-sensitive in vagal neuropathy cases. Remember, asthma itself is a vagal event. From my perspective as an experienced clinician, vagal neuropathy resets asthma triggering, to a hair-trigger; it becomes sensitized to react to low-level stimuli causing more frequent asthma attacks.

In closing this section, I should remind you that most cases of asthma are not asthma at all, but rather Reflux-Related Breathing Problems; asthma is trouble getting air OUT of the lungs during exhalation, and reflux causes breathing IN (inhalation) problems.

† KoufmanJ. The diagnosis and management of non-pulmonary chronic cough. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Broncho-Esophagological Association. April 19, 2012, and also reported in The Chronic Cough Enigma, pp 5-16.

CARDIOVASCULAR SEQUELAE OF VAGAL NEROPATHIES SEQUELAE OF VAGAL NEUROPATHIES

This section is about syncope (fainting), and cardiac arrhythmias related to vagal neuropathies. Note that these manifestations of vagal neuropathies are both uncommon.

What Causes Vasovagal Syncope (Fainting)?

First of all, there is a common type of “normal” swooning, that is, passing out, fainting, or vasovagal syncope. According to WebMD, Fainting is a common problem, accounting for 3% of emergency room visits and 6% of hospital admissions, and it can happen in otherwise healthy people; fainting, losing consciousness, is syncope.”

The bottom line is that normal people can drop when the brain doesn’t get enough blood, usually from fright or any emotional shock. For example, it is not uncommon for a close family member to faint at the funeral of a loved one. Most of the time, fainting is “situational.”

Vasovagal syncope by name alone is vagally mediated. Here’s what happens: a shock causes vagally-mediated bradycardia (slowing of the heart), a drop in blood pressure, pooling of blood in the legs, and not enough blood and oxygen gets to the brain. Down you go, vasovagal syncope; fainting is vagal.

Beside stressful events there are other factors that may contribute to vasovagal syncope, including standing too long, fasting, dehydration, taking blood pressure medicine, and violent coughing.

That last one, coughing, is an interesting one (but not usually serious cause). Usually, people who faint are the hardest coughers. Over my long career, I have seen about 50-60 patients who coughed until passing out. In those cases, I presumed, and still presume, that the mechanism is somehow vagal.

BTW, often a person may feel lightheaded (“pre-syncope”) before falling out; usually these people look white, too. If this is identified by the “soon-to-faint” or anyone else, the person should lay down flat with the legs raised. This will return blood to the brain and prevent full vasovagal syncope. If you take the fainter’s pulse, it will be weak and thready. Don’t sit them up until the pulse is again strong and regular.

In summary, isolated simple syncopal episodes are common and circumstantial so that subsequent medical evaluations are not necessary.

What Is Atypical or Recurrent Vasovagal Syncope?

What causes someone to pass out repeatedly? Well, there are real medical problems that must be investigated, including heart problems, arrhythmias (irregular heart beat), seizures, low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), anemia (a deficiency in healthy oxygen carrying cells), and problems with how the nervous system, particularly the body’s system for regulating blood pressure. Sometimes masses pressing on a vagus nerve can cause recurrent vasovagal syncope?

Illustrative Case Example: Recurrent Syncope Associated with Overeating

A 62-year-old woman suffered from intermittent fainting; it almost always happened in restaurants after a big meal. She was otherwise a completely healthy woman. In 2013, she had her first vasovagal event after a big dinner.

Over the next few years, the same thing happened many times, and she was aware that this only happened when she had overeaten. Most of these syncopal events were in restaurants; and after most of the syncopal events she’d get diarrhea.

After a while, she noticed that she got lightheaded before she fainted, and by paying attention to the lightheadedness as a prodrome to fainting, she would immediately lie on the floor. This always seemed to happen at the end of the meal, and mostly in restaurants. She would of course explain what was happening to her fellow diners. She’d just lie on the floor until faint feeling passed; thus, she was able to prevent falling out. And again, it should be noted that this always happened after a big meal.

One night at the movies, she began having upper abdominal and right shoulder pain. She subsequently saw her doctor who ordered an abdominal CT scan, which showed a large 5” (12 cm.) mass high up in her liver.

In March 2018, she had laparoscopic removal of a benign cyst which was adjacent to, and pushing on the dome of her stomach just where it was resting against her lower esophagus. After the surgery, she never felt faint again.

Comment: The liver cyst was adjacent to her esophagus, and presumably when she overate, the full stomach would push the mass against the esophagus, against one of her vagus nerves; and that’s what caused her fainting after overeating.

Over the years, I have seen only a handful of other patients with masses pressing on the vagus, but those cases (two diverticula) also recovered after surgery.

The Point Is: Recurrent syncope needs a medical work up.

Can Vagal Neuropathies Cause Cardiac Arrhythmias?

In my career, I have seen but a few of these cases, and I must say that they ask more questions that I can answer; the thing is that each had a strong, credible story of preceding PVVN.

Illustrative Case Example: Vagally-Mediated, Reflux-Related Arrhythmias

A 45-year-old businessman came to see me because he was having tacky-bradycardia (too-fast then too-slow) that he thought was associated with reflux. After a reflux event, his heart would start racing, and them slow to the point that he was getting postural hypotension and had to lie down to avoid fainting. Most episodes lasted 10-20 minutes.

By my exam and testing criteria he had reflux, vocal cord paresis, and a PVVN pattern on LEMG. Because this patient’s story and symptoms were so bizarre, I arranged with his cardiologist to perform ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring on the same day that was having cardiac (Holter) monitoring.

The two tests side-by-side showed the association between pharyngeal reflux events and the arrhythmia. Unfortunately, after that, he did not return to me for follow-up, but I heard from a colleague that he had a successful cardiac ablation procedure, a procedure used to treat arrhythmias.

What We Don’t Yet Know

I have spent much of my career trying to understand vagal function and dysfunction, and I am forced to conclude that so little is known about it and that there is almost no meaningful research (to my knowledge). The latter issue may be in part related to the fact that the vagus doesn’t fall within the domain of any specialist; it’s too big and the specialties too small.

Early in my career, I tried to establish a vagal-reflux testing laboratory and was doing single-nerve unit recordings from the superior laryngeal nerve. The work that we did, some of it unreported, showed a remarkable two-way vagal network, with distant and distal afferent stimulation causing near and unexplainably unrelated motor responses. For example, capsaicin placed in the distal esophagus (or stomach for that matter) could cause laryngospasm.

What this suggests is that the vagus is like a neural computer for all organ functions. It’s not like the leg bone is connected to the hip bone; rather, it’s like the leg bone is connected to the jawbone. The vagal network connects almost everything to almost everything else in a still secret and complex manner… that defies known physiology and neuroanatomy.

Having spent a good deal of time writing this blog, I must declare that I cannot reconcile “how this is connected to that.” So, why not include vagal connections to other distant brain centers, even those that affect our psychology and mental health? I am as yet uncertain, but the vagus may be the seat of the soul.